The implementation of the SAAQclic project, aimed at a major digital transformation of the services of the Société de l’assurance automobile du Québec, encountered significant difficulties.

This analysis looks at the compelling causes of this failure, examining the organizational, technical, and managerial factors that contributed to the observed dysfunctions.

Accurately identifying these causes is key to learning lessons and avoiding future pitfalls in projects of this scale.

The publication of the VGQ’s report on the failure of the CASA program, which includes the launch of the SAAQclic platform, prompted us to examine each point in detail, with the aim of identifying possible solutions to this type of situation, which unfortunately occurs all too frequently.

This document analyzes errors and proposes solutions to improve digital project management. It addresses three main axes:

Introduction

Following the publication of the Auditor General’s report on the audit of the SAAQclic platform development project, many expressed their concern about the ministers’ reaction. The latter tried to deny their responsibility by claiming that they had been misled by incorrect information regarding the status and status of the project.

Few were convinced by these remarks and asked for their resignation, citing ministerial responsibility. Indeed, the custom inherited from our British parliamentary system suggests that members of the executive must answer for the mistakes committed by their civil servants, who work in their respective ministries.

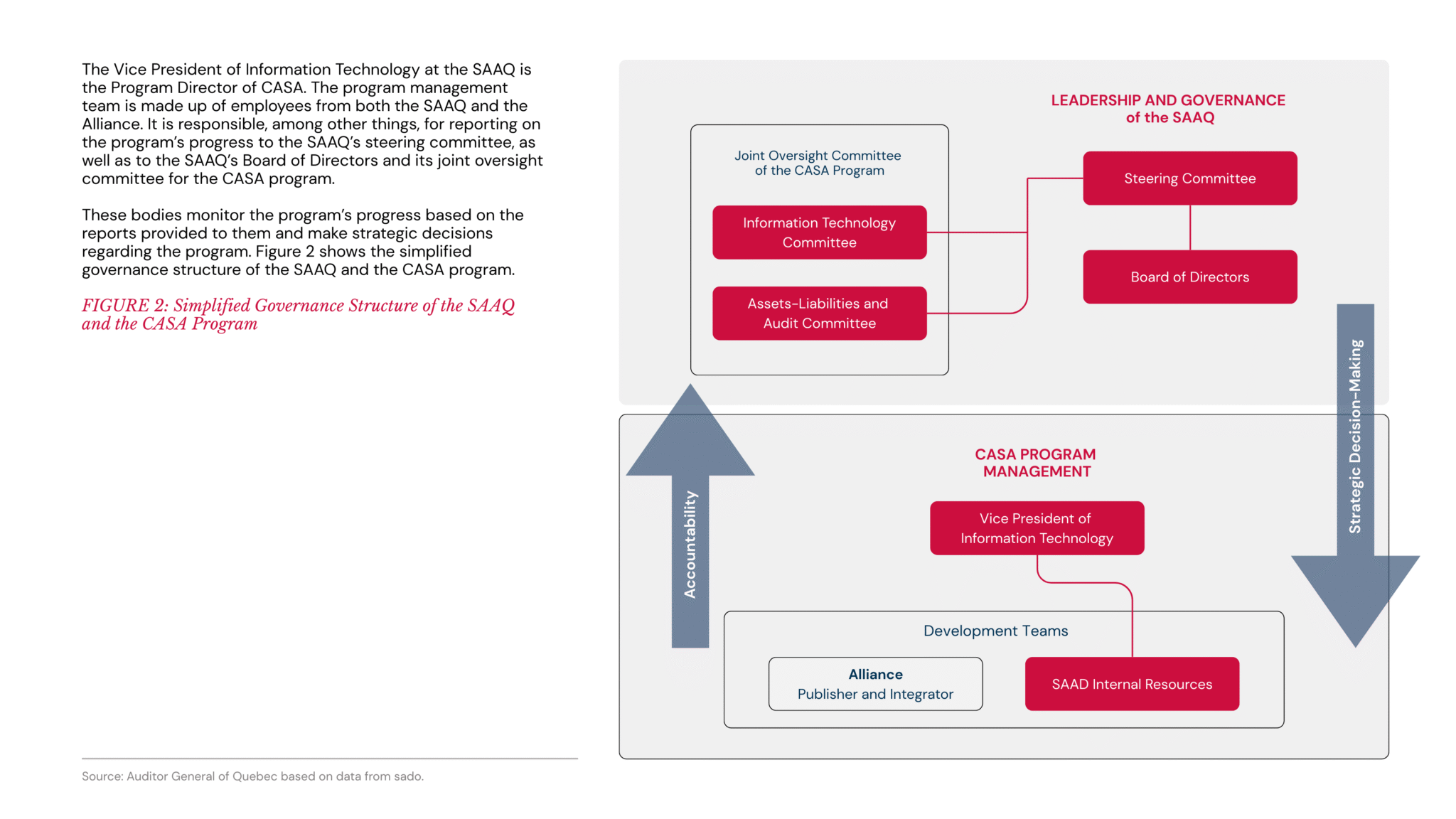

However, the SAAQ’s status as a government agency slightly complicates the application of this principle, which applies more to traditional ministries. The SAAQ reports first and foremost to its Board of Directors, which exercises decision-making power over the SAAQ’s orientations and actions, so that the SAAQ fulfills its obligations and achieves the expected level of performance.¹

It should also be noted that the departure of a minister, although it may allow the government to maintain the bond of trust between the government and the population, is not a lasting solution to such a problem.

As a project management practitioner, we have been more interested in managerial causes, i.e. related to the management of the initiative, in order to understand the causes of this failure. To do so, we carefully reviewed the report to identify the factors that may have explained such a result.

In our view, the resignation of a minister, while necessary to respect constitutional conventions and maintain public trust, is not enough to prevent a repetition of this scenario, especially with the growing need for digitalization of public services.

In this article, we will identify the major problems encountered in the CASA program and try to explain how good governance could have minimized the probabilities of these problems occurring. Our goal is to leverage our respective experiences to identify the factors that we believe have had a decisive impact on the outcome we are experiencing today.

It should be noted that we have no connection with the project in question, either directly or indirectly. The claims made in this article are based exclusively on the data in the report and other information relayed by the media.

The opinions expressed on the measures that should have been taken are based on our interpretation of the facts and are based more on our experience than on our assessment of the facts.

We hope that these observations will help to initiate the dialogue needed to improve the overall success rate of projects undertaken, both in the public and private sectors. This should also benefit the community of practice to which we proudly belong.

Governance

On February 20, Éric Caire, while still Minister of Cybersecurity and Digital Affairs, said the following:

"The SAAQ gave the wrong information to the management. What the AG [Auditor General] is saying this morning is serious. There were delays, it was known, it was known. There was a poor quality in terms of deliverables, it was known, it was known. And the information that was delivered was that the project was progressing on schedule and that the project's objectives were being met. We were most certainly deceived.

(Le Devoir – February 25, 2025)

Beyond the veracity of the statement, it is surprising that an individual, with such a strategic role, was so far removed from the monitoring of the project and that the existing processes were not enough to inform him of the significant deviations.

Such a situation cannot be explained other than by an ineffectiveness of the governance framework put in place by the project team.

Before justifying why effective program governance is necessary, let’s start by defining the principle:

Governance, in the broad sense, is a framework for work. It includes, but is not limited to, the rules, processes, standards, policies, etc., that people working in a system must follow.

There are several levels of governance. In this analysis, we will focus on the analysis of the program since it is, in our opinion, the framework over which the agency has the most control.

In addition, we believe that it is this specific level that could have allowed for better communication between stakeholders (mainly program management, the executive committee and the board of directors²) and thus resolve the communication issues raised to justify the current situation.

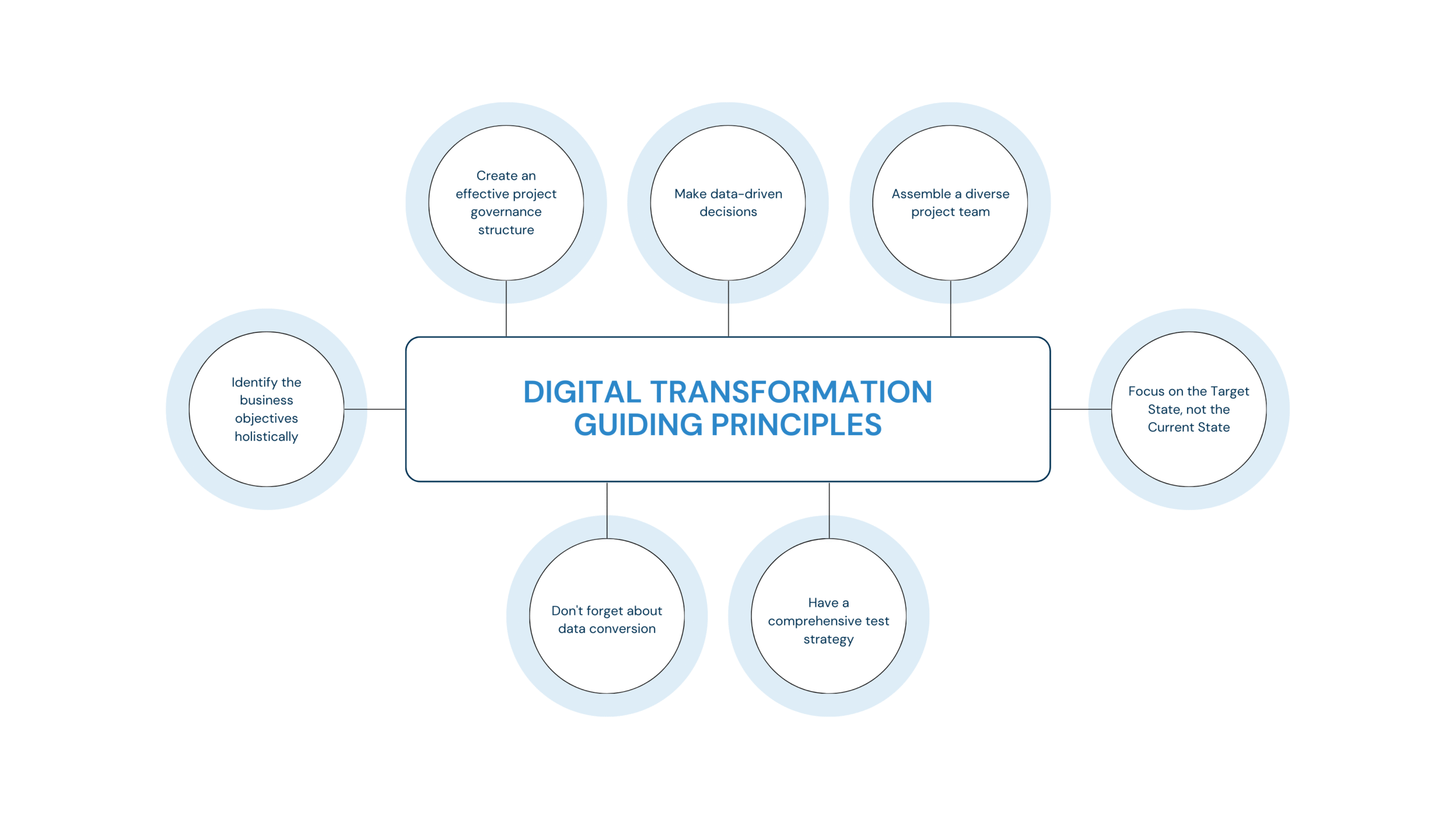

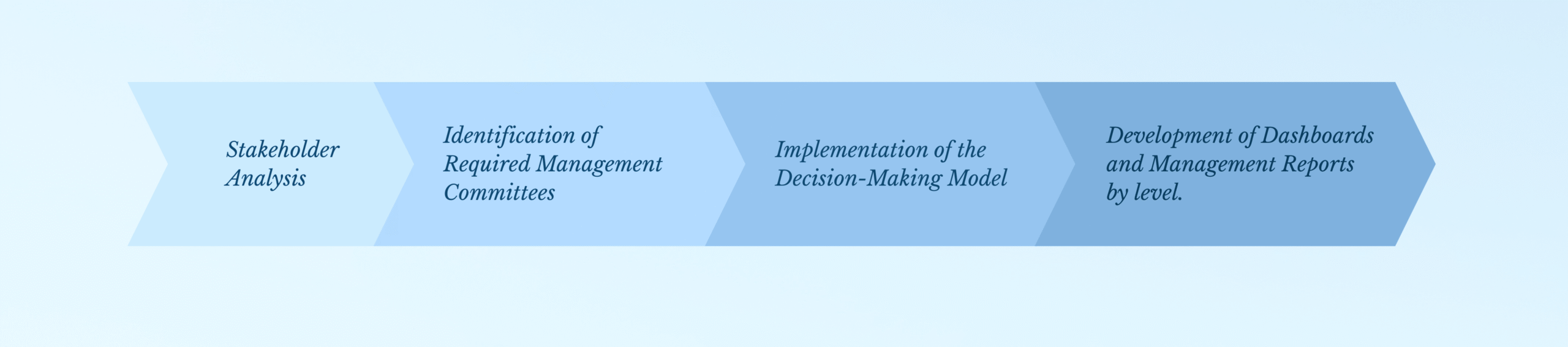

In our view, there are four important pillars in defining the governance framework:

Identification of Stakeholders

Identifying stakeholders is a fairly simple exercise in itself. It is a question of identifying the people involved in the project according to their expected contribution and their role. In other words, it is about planning the commitment of the people involved in an organization to a specific initiative.

That being said, there are often several questionable practices on the ground that have an impact on the quality of the governance framework. Here are a few examples that could explain some of the situations raised in the SAAQ case:

- Lack of communication on major issues, including increased costs that were not communicated to decision-makers

This could have been avoided if there had been a specific definition of responsibilities and accountability for the budget. - There was confusion about the ministers’ responsibility for the agency and seemed to contradict the conventions and the expectations of the population.

- The ministers did not seem to agree on the identity of the ” file holder “.

- Some tasks intended for the agency were delegated to the software publisher without these decisions being duly justified.

Approach

- Promote the awarding of a contract to an existing supplier

- Publish an invitation-only request for proposals

- Development of very strict evaluation criteria

- Favor large/recognized vendors as leaders

Benefits

- Accelerates contract logistics by enabling existing framework agreements to be leveraged

- Avoids the need to analyze irrelevant bids received in public tenders

- Helps foster services

- Better short-term negotiation levers on the conditions for carrying out a new project

- Avoids analyzing irrelevant bids received in public calls

- Limits the number of non-qualifying bids received

- Easier to justify the choice of a supplier or solution to stakeholders.

Risks

- Participates in maintaining inadequate/ineffective relationships

- Increases the risk of developing a dependency on a specific vendor(s)

- Potential loss of room for manoeuvre and bargaining power in the medium to long term

- Fails to identify potentially less expensive and equally effective alternatives to meet needs

- Lost opportunity to identify new alternatives/recent market developments

- Design of a call for proposals designed with the intended vendor in mind vs. specific needs and project objectives

- The reputation of a product does not offer any guarantee of quality based on a specific business context/objectives.

Identification of the various management committees required:

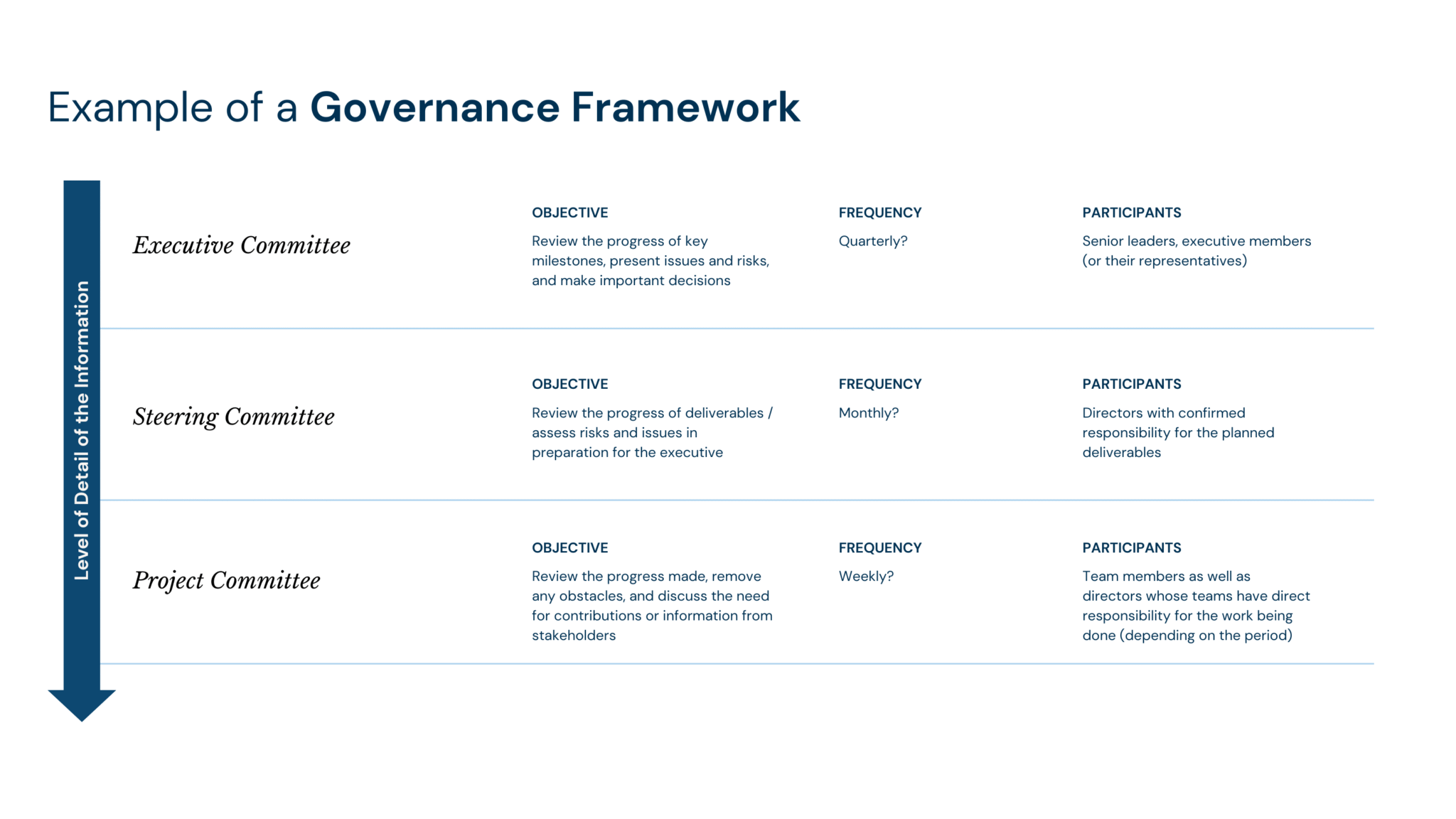

After taking stock of the stakeholders, it is necessary to establish the logistics by which they will be called upon to communicate with each other. The principle is that follow-up meetings must be scheduled according to a recurrence that depends on the level of granularity of the information required.

In principle, the closer one gets to the realization of the work, the more the need to exchange increases. The idea is not to monopolize the agenda of the project participants, at the risk of impacting overall productivity. Rather, it is a question of ensuring an adequate level of control over risks and issues that could challenge initial planning.

The cadence and participants required for the different pillars of governance can be determined based on the specificity of the project or the organization undertaking it.

To return to the specific case of the SAAQ, it seems unthinkable to us that the “decision-makers” would not have been informed of the increase in costs if such logistics had been put in place.

From reading the VGQ report, we understand that program management did not provide accurate and consistent information. However, we are surprised that the members of the various committees did not ask for more precise information on the overall health of the project.

Setting up the decision-making model

To ensure that the right decisions are made in a timely manner, it is essential that the decision-making mechanism is clearly defined. As mentioned above, a common mistake is to share the accountability of a project between the different managers of the departments concerned.

Dilution of accountability usually leads to greater latency in decision-making, and can even lead to conflicts due to misinterpretation of roles and responsibilities between teams and managers.

It is therefore much better to establish clear roles and responsibilities at the very beginning of the project. In return, it is necessary to free up the time required for these designated persons to take on the workload required for their involvement in the project. These people will also have to have the formal and moral authority to make decisions on complex decisions.

We will discuss the issue of decision-making in more detail later (section on the decision-making process) and we will give examples to illustrate the shortcomings that can be explained by a deficiency in management at the decision-making level.

Development of dashboards and management reports required by levels

To ensure the effectiveness of these committees, the information presented on these committees must be fair, consistent and appropriate for the hearing. There are different methods for presenting the overall health of a project. One example is the calculation of earned value, which consists of measuring the progress of the work according to the initial plan.

The principle is very simple. Following the initial planning exercise, a preliminary assessment of total effort should be formalized. Although at this stage the budget assessment remains summary and rather imprecise, the resulting figures will serve as a reference throughout the life cycle of the project. Based on this assessment, the team will then be able to measure the effectiveness of this planning based on the actual costs and deadlines identified during the execution of the work.

Obviously, this initial planning will have to be reviewed because several unforeseen or underestimated elements will occur along the way. These possible deviations, while they may seem embarrassing to those involved in the planning, must be seen as quite normal. It is simply a signal that it will be necessary to review the game plan and identify the possible alternatives on which a decision will have to be made.

In addition, the targets should never be changed without the change and its impact on the new plan being formalized and approved by the Executive Committee.

This is where we think the problem lies. The facts presented in the VGQ report seem to show that the targets have been changed without these changes being documented and formally approved.

In addition, the visibly incomplete nature and the lack of consistency in the information produced and communicated are factors that call into question the quality of the managerial supervision of the initiative.

As professionals in the sector, it is difficult for us to understand how it was possible to hide such a significant increase in time and cost from the members of the executive committee, the board of directors and the ministers responsible.

A simple reconciliation between the timelines and costs for professional services could have foreseen significant overruns. The ignorance pleaded by the ministers therefore seems to us to be hardly credible.

With respect to the accuracy of information provided to external stakeholders (including Cabinet), we agree that no tool is immune to dishonesty and lies. The report is very clear on this subject. External submissions did not present information that was accurate to what was reported within the project.

Although this situation is highly regrettable, we believe that certain control mechanisms, particularly related to the lack of liaison between the project and the executive, contributed to this result. This could have been avoided if the governance framework was commensurate with the importance of the initiative.

Supply

Supply management is often perceived as a tedious, cumbersome task in the context of project implementation, which is responsible for significant deadlines. Indeed, the tasks and the resulting deliverables are time-consuming and usually require a considerable investment in terms of effort

However, control mechanisms inspired by best practices have a usefulness that should not be neglected. Taking excessive shortcuts, often motivated by the desire to optimize the schedule, can sometimes lead to issues whose impact is often worse than the expected gains.

Reading the report, it appears that some of these controls were circumvented in order (perhaps) to optimize overall schedules. While we cannot verify the accuracy of this last statement, we believe it is appropriate to re-examine the value of these controls in the context of the issues identified by the Auditor General.

Appropriation of business requirements

The report indicates that the program transferred the responsibility for identifying the business requirements that would support the choice of the solution to the service provider.

Beyond the risk of obvious conflict of interest, it seems important to highlight the lack of ownership of the orientations that should guide the design and development of the solution.

The SAAQ’s mission, as well as its operational framework, even if they are similar to those of institutions in other jurisdictions, must be considered specific. In this sense, very early in the initial phases of the project, it was known that many adaptations and customizations of the chosen software package would be necessary.

Rather than taking ownership of the detailed design of the platform in question, the SAAQ preferred to delegate this responsibility to the platform’s publisher.

Unsurprisingly, the latter returned a report confirming the ability of its system to replace those of the agency.

It is possible that the SAAQ may have had limited skills and resources to carry out this work. However, we share the opinion of the Auditor General, who rightly states that ” a specialized firm could have conducted denominalized and independent analyses aimed at comparing several solutions, (…) likely to meet the needs of the SAAQ .”³

The biased and self-serving approach that guided the development of the solution was a significant error, which led to the significant (if not total) loss of control of the management team.

The choice of solution and partners

One of the main findings of the VGQ is that “the SAAQ has taken few steps to examine all the possible IT solutions for the modernization of its computer systems before deciding to use an ERP.”⁴

Although it may surprise some, it must be admitted that this type of situation is quite common. Assuming the good faith of the parties (to exclude potential factors such as collusion), we could hypothesize that this approach was chosen to speed up decision-making and optimize the overall timeline. This could have made it possible, for example, to opt for a publisher and partner that already had an existing contractual relationship and thus avoid the delays related to the drafting and signing of a new complex contract.

Obviously, we agree with the idea of making a trade-off between the scope of the selection process and the desire to optimize the overall schedule. However, we also believe that the framework leading to the decision must be defined in terms of the organization’s specific risk appetite and tolerance. The fictitious example below demonstrates the type of decisions where the focus could be on benefits:

Approach

- Promote the awarding of a contract to an existing supplier

- Publish an invitation-only request for proposals

- Development of very strict evaluation criteria

- Favor large/recognized vendors as leaders

Benefits

- Accelerates contract logistics by enabling existing framework agreements to be leveraged

- Avoids the need to analyze irrelevant bids received in public tenders

- Helps foster services

- Better short-term negotiation levers on the conditions for carrying out a new project

- Avoids analyzing irrelevant bids received in public calls

- Limits the number of non-qualifying bids received

- Easier to justify the choice of a supplier or solution to stakeholders.

Risks

- Participates in maintaining inadequate/ineffective relationships

- Increases the risk of developing a dependency on a specific vendor(s)

- Potential loss of room for manoeuvre and bargaining power in the medium to long term

- Fails to identify potentially less expensive and equally effective alternatives to meet needs

- Lost opportunity to identify new alternatives/recent market developments

- Design of a call for proposals designed with the intended vendor in mind vs. specific needs and project objectives

- The reputation of a product does not offer any guarantee of quality based on a specific business context/objectives.

It is not uncommon for the beneficiaries of the solution to leave the integrator free to make the decisions resulting from this arbitration. In our view, this is a significant mistake and it is much better to give the different levels of decision-making the responsibility of choosing the appropriate approach or framework.

In addition, some specific examples, such as the decision to divide the value of certain endorsements, illustrate a clear intent to circumvent the control mechanisms. This strategy aims to minimize the media and political risks associated with disclosing an increase in costs.

However, the turn of events and the spectre of a public inquiry demonstrate the incoherence of such an approach. Rather than eliminating media and political risks, such an approach seems to have rather accentuated the impact of this risk. It is crucial to draw on this experience to highlight the importance of a rigorous and objective analysis of the risks associated with the decisions made.

Conclusion :

The reputation of a publisher or integrator alone cannot ensure the success of an implementation project. The risks associated with a misunderstanding of the organizational framework are sometimes greater than the simple desire to reduce delays.

The time and effort spent on this approach should be commensurate with the size of the proposed project and the significance of the underlying risks.

With regard to external assistance, it is important that the chosen partner be neutral and impartial in the choices resulting from these recommendations.

Quality

In project management, it is essential to maintain a balance between the project scope, the schedule and the allocated budget. This interdependent relationship is often referred to as the “Golden Triangle” or “Triple Constraint”.

- Timeline The duration of the project

- Budget The cost of the project

- Scope The final product (its quality and compliance with what was intended)

The theory says that you can’t change one of these elements without affecting the other two. Like a Rubic cube, any changes made to a given face will impact the rest of the prism.

For example, if you decide to reduce the amount allocated to the project, you will inevitably have to do the project faster or reduce its scope (by reducing the quality or size of the final deliverable).

In the case of the CASA program, timeline appears to have been the immutable variable and was prioritized over scope.

The chaos that followed the publication of the website suggests that it was a mistake and that this decision was not taken in a concerted manner. The selection of the preferred variable must be determined at the start of the project and formally ratified by the Executive Committee when establishing governance.

Although quality was not the key element in the management committee’s decision-making, it cannot be denied that there were also several shortcomings in achieving the result we know.

Here are the main shortcomings identified by reading the VGQ report:

1. Testing was not completed prior to commissioning⁵ ⁶

It is hard to believe that no testing strategy has been developed by the project team. Certainly, it was not adequate or it was not respected. With proper governance, two critical processes would have been in place, which would have reduced the risk of premature commissioning, which had disastrous consequences.

A deliverable acceptance process would have verified and approved the following deliverables:

- Test plan (use cases)

- Test Result Report (how results are presented)

- Testing strategy (unit testing, user testing, integrated testing, timeline, etc.)

A Gating Process would have provided clear requirements before approving commissioning.

2. The quality of the tests is insufficient⁷ ⁸

Not only did program management not complete the tests, but the report also reveals that the tests performed were not of high quality. A good testing strategy not only identifies what to test, it determines how the tests that will be performed and whether those tests will produce an adequate level of confidence to allow a go-live.

In addition, the VGQ report does not mention the approval of the tests or their results. It is often referred to as a percentage of test completion, but not as a percentage of acceptance. That is, the number of tests that have produced positive results, confirming that the solution is appropriate and does not require any correction.

However, we know that the rate of successful tests was not 100%, since it is indicated that anomalies remained at the time of launch. So not only were the tests not completed, but those that were not even all providing conclusive results.

Also related to the quality of the tests, the report states that the integrated tests were carried out in parallel with the development.[9] It is possible to test in parallel with development, it is even a common practice that saves time. However, it is usually the unit tests that are carried out in parallel.

For the uninitiated, unit testing is aimed at an isolated process or a simple functionality, unlike integrated testing which is aimed at the entire process.

For example, can first test the action of renewing a driver’s licence online on the SAAQclic platform (Unit test), and then test the entire renewal process (connecting the user to the platform, renewing the licence, paying for it, sending information to the systems of external organizations such as the police, etc.).

This simple example illustrates three important principles:

- The functioning of the platform can only be guaranteed if the overall process (and not the singular validation of each of the functionalities) is reproduced.

- Integrated tests can only be completed if the entire development is completed.

- Even the slightest change means that the integrated tests must be completely redone to ensure proper operation.

Given the Alliance’s experience, it is obvious that this basic principle was known to the team. We therefore assume that once again, meeting the planned schedule has resulted in a change in the testing strategy. Something that could have been avoided by a change management process.

3. Corrections not made before commissioning¹⁰

The report confirms that the implementation of the CASA program was approved despite the fact that corrections were still required until then.

It is always possible (although undesirable) that a go-live will be approved despite the presence of certain bugs, provided that they are deemed acceptable by a decision-making committee. Effective governance helps identify these elements. Governance will establish acceptable thresholds and critical elements that must be operational prior to commissioning.

In this case, we are talking about more than 129 bugs that have been postponed for fixing. There is no evidence that all 129 bugs were deemed acceptable by the steering committee.

Considering the (significant) risk of identifying additional bugs after go-live, postponing fixes to release will put significant pressure on the resources that will support users once the system is in production.

We only have to think of the story of the problems experienced today and the anger recorded by the population when the platform was put online to confirm this statement

4. Use of fictitious data¹¹

While it’s best to test with real data, it’s not always possible to do so. However, in the case of the CASA program, this is what was initially planned. So we come to the real issue, which is not so much the use of fictitious data as the modification of the strategy along the way.

This change is substantial and should not be possible without the approval of the Management Committee. Good governance requires a process for approving changes in scope, schedule or budget by the appropriate bodies.

This leads us to the following conclusion: Good governance would have made it possible to:

- Ensure that the items to be tested are appropriate

- Ensure the quality of the tests

- Present test results objectively

- Define minimum test acceptance thresholds

- Define acceptance criteria for commissioning approval

- Not making a major change without approval through a change management process

Decision-making process

For the governance framework to be successful, it is imperative to look at how decisions are made within a project. Its importance is that the approval mechanism ensures the successful passage of several important steps:

Definition of the need and strategic objectives : What problem do we want to address or what opportunity will we try to seize with the realization of our project?

Definition of the scope: What will we achieve, what will be the deliverables of the project?

Budget confirmation : How much are we willing to pay (or can we pay) for this project?

Change Request Process: What are the acceptable changes (scope, budget, schedule, resource, vendor, etc.) and how will these changes be approved?

Phase Transition : It is common in project management to have a process called “Gating”. That is, the steering committee must approve one or more deliverables before the project can move on to a next stage.

Allocation of funds: Although an initial budget is approved ($638M in this case), it should not be available in its entirety on day #1 of the program. The budget should be allocated in phases, with the aim of capturing any overruns as early as possible.

The following are the key issues of the CASA program that could have been avoided if a proper decision-making process had been put in place:

Approval of early commissioning¹²

It is quite obvious that the commissioning should never have taken place in February 2023. Although program management had established criteria to be met prior to commissioning, the commissioning took place anyway, even though some criteria were not met¹³.

It is a widespread best practice to determine a list of criteria that must be met in order to authorize a commissioning. These are called ” Go/No Go Criteria “.

Normally, this list is proposed by the program management and approved by the executive committee. All of these criteria must be met before the Go Live is approved.

In this case, the list was made but not respected. It is difficult to understand why the management committee did not review this list before the formal approval of the commissioning. Normally, program management must confirm to the committee that all criteria are met. If some are not, we can always put a mitigation plan in place and accept the risk of not having met all the criteria. However, in this case, the SAAQ board of directors approved the commissioning on January 6¹⁴, while as of January 17, 19 of the 52 established criteria had still not been met¹⁵.

Therefore, if the project’s governance had established a process for accepting the steps, including the Go Live, and if it had been respected, we can estimate that the commissioning would have been postponed and that several issues could have been resolved before the solution was accessible to the population.

Budget Management

There is very little information in the report as to how the budget was managed. We are referring here to the initial approval, the allocation of funds (by phase or only at the beginning of the project), forecasts and requests for amendments. However, the fact that the steering committee was not informed that the completion of the project would require an additional $500 million¹⁶ clearly indicates that there was a shortfall in this area.

A combination of the following three processes: allocation of funds, acceptance of milestones, and request for changes, would have resulted in program management not being able to:

- Spending the money earlier than planned¹⁷

- Spending money without reporting on progress

- Spending the money without the committee knowing that the total estimated costs of the project were skyrocketing

We have already discussed the subject of program costs and communication around them in the dashboards section, but here we are talking about putting controls in place, which can compensate for a lack of transparency in communication.

Scope Management

Earlier in the text, we talked about the importance of clearly defining needs. It is this definition that will lead us to establish the scope. While it is critical to define the needs and define the scope, it is just as critical to ensure that it does not change along the way for no good reason. It is wrong to think that a scope should not change during a project. Especially when it lasts several years. It is normal to have to adapt what we had planned at the beginning or to see our needs change because of the evolution of the external environment, such as a change in the competition, a new technology, a change in the behavior of the target customers, etc. However, we must remain cautious in the management of such changes because if they are not carefully thought out, they can derail the project from its initial objectives, and thus lead to failure.

That’s why it’s important to have the right process in place to manage these changes. Through the change request process, stakeholders may be asked to review the change and confirm its impact. No changes are expected to be effective until the authorities for this project have formally approved it.

In the context of the CASA programme, the scope has been changed several times, both upwards¹⁸ ¹⁹ and downwards²⁰. Unfortunately, the VGQ report does not mention what the approval process was to change the scope of the program, or even if there was one.

By putting a change request management process in place, we make sure to document the change we want to make and especially the impacts that this change will have on the project. If we reduce the scope, we may remove some features from the final product. It is therefore necessary to ensure that even if these functionalities are removed, the initial essential needs will still be met.

By increasing the scope, there is a good chance that the budget and/or deadlines will also increase. While both of these aspects are extremely important, there are other, more insidious impacts that an increase in scope can bring, such as work overload, technical complexities, organizational changes, etc. In short, changes in scope are not to be taken lightly.

In the jargon, when you move away from the initial scope, it’s called the ” Scope Creep “. Usually, it starts with a small modification. Often we think it is unimportant, but the more we advance in the project, the more it grows.

It also happens that there are several small changes that we agree to make over time, because they are so small that we think that the impact will not be visible. However, well before the end of the project, we realize that it is the accumulation of all these small requests that will make it impossible to respect the budget or the schedule.

A good example of questionable scope management is the inclusion of the ” Government Authentication Service “. Although the subject was not addressed in the report, except for the moment when it is explicitly stated that this portion of the project was excluded from the audit²¹, it would seem that the connection to the SAAQclic platform was not initially supposed to be done via the government authentication service.

Such an addition to the scope is of considerable importance, since it is a question of linking two programs together, with two major joint commissionings. This is the kind of decision that requires a change request and approval process and must be made following a risk and impact analysis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the failure of SAAQclic, although it can be partly attributed to governance shortcomings and inadequate scope management, occurs in a context where the complexity of large-scale projects is an unavoidable reality.

While this review is not intended to point fingers at fault or to question the work of those who contributed to it, it is crucial to learn from this experience. Indeed, the digitalization of public services is a necessary step and maintaining investments in this direction is not a choice, but a necessity.

We therefore hope that the recommendations we have made, which focus on better definition of needs, stronger governance and proactive risk management, can be used as a guide for subsequent initiatives.

In this sense, we are convinced that by integrating the recognized principles into the orchestration of future projects, we will be able to collectively work (as professionals) to avoid the repetition of common mistakes and thus increase the chances of success of future complex projects.

Annex

¹ https://saaq.gouv.qc.ca/saaq/gouvernance-structure-administrative/conseil-administration

² See Appendix

³ VGQ Report, p.36

⁴ VGQ Report, p.16

⁵ “CASA program management did not conduct the necessary testing prior to the commissioning of the new IT system in February 2023.” – VGQ Report, p.15

⁶ “At the time of confirming the commissioning of Delivery 2 on January 17, 2023, nearly 20% of the final integrated tests had not been completed. They have not been completed. On February 10, 2023, the SAAQ decided to stop carrying out the final integrated tests, even though 6% of them had still not been carried out. – VGQ Report, p.39

⁷ “The quality of the tests carried out, in particular, was insufficient to reduce the risks associated with proceeding with a single commissioning for all points of service.” – VGQ Report, p.15

⁸ “The quality of the tests performed was not sufficient to reduce the number and severity of IT issues associated with the implementation of CASA Release 2 to an acceptable level” – VGQ Report, p.40

⁹ “The final integrated testing was to be carried out after the development of the components of Delivery 2 had been completed. Rather, there was overlap between testing and development. This practice presented significant risks, including that the quality of the tests would be affected. Indeed, since the development was ongoing, new problems could be created and affect computer processes considered to be completed. – VGQ Report, p.41

¹⁰ “The SAAQ has postponed the correction of 129 anomalies, most of which were corrected between February and May 2023 and which were in addition to the computer problems detected after commissioning.” – VGQ Report, p.39

¹¹ “First, the program management had initially planned that the final integrated tests would be carried out using real data instead of data created for testing. The use of real data ensures that the tests reflect the reality of the SAAQ. Fictitious data was finally used to carry out part of the final integrated tests, but the SAAQ could not confirm to what extent. – VGQ Report, p.40

¹² ” The commissioning of the new IT system in February 2023 has led to significant problems and has not yet generated the expected benefits. – VGQ Report, p.17

¹³ ” However, the available information leads to the conclusion that some of these criteria were not met at the time of commissioning. – VGQ Report, p.52

¹⁴ ” On January 6, 2023, the SAAQ Board of Directors authorized the commissioning of Delivery 2, on the sole condition that it be informed of any situation deemed important in this regard. – VGQ Report, p.51

¹⁵ ” Program management had identified 52 criteria to be met in order to reduce the risks associated with this commissioning. According to program management documentation, 19 of them were not met as of January 17, 2023 ” – VGQ Report, p.51

¹⁶ ” The costs of the CASA program have increased by nearly $500 million and this increase has not been clearly communicated to decision-makers. – VGQ Report, p.26

¹⁷ ” The contract signed in 2017 between the SAAQ and the Alliance for the realization of the program allowed for a reallocation of the various budgets between phases and deliveries over a period of 10 years. This gave program management greater flexibility in delivering the program, but presented the risk that the budget would be spent too quickly and that only a portion of the phases and deliveries could be completed. – VGQ Report, p.27

¹⁸ ” Initially, the processes for monitoring the safety of the road transport of people and goods were not to be integrated into the new IT system. It was only planned to create bridges between the latter and the old IT system that supported these processes. However, in planning the CASA program, program management did not realize the high level of complexity involved in creating these bridges. As a result, these processes had to be integrated into the new system, resulting in additional costs estimated by program management at $38 million. – VGQ Report, p.34

¹⁹ ” Prevention and sanctioning of offences relating to road transport through Contrôle routier Québec. Note: Initially, it was not intended that this function would be fully covered by the IMP. She was integrated into the program along the way. – VGQ Report, p.21

²⁰ ” In addition, the development of some of the components of Delivery 2, including Bundled Billing, which was estimated to have significant benefits, has been deferred and included in a new delivery that program management refers to as ‘Delivery 2.5’. To date, the timelines and costs associated with this new delivery are not known. – VGQ Report, p.34

²¹ ” The development of the Government Authentication Service, the use of which is required to access the SAAQclic platform, was the responsibility of the Ministry of Cybersecurity and Digital Affairs and is excluded from our work. – VGQ Report, p.22